George Strait sings about it. Kevin Costner built a baseball field in the middle of it. The Pioneer Woman cooks for it.

When one hears “American Heartland”—specific images and cultural values come to mind. With more emphasis on the economy between the coastal regions of the United States, there’s more interest in the American Heartland that goes beyond a country music song, a movie, or a popular cooking show on television.

And yet, a widely shared vision of what geographic region truly comprises the American Heartland has so far proved elusive.

A recent online poll from The New York Times provided nine different maps of the United States. They then asked their readers to choose the one map that most closely represents their perception of the American Heartland.1 Many of these maps represented subsections of states. Out of the provided choices, the map with the most responses only managed a meager 22 percent. Some people might see it merely as the middle of the country (Midwest). Others may use the pejorative term, Flyover Country. Most would not include parts of the South. Many would focus on the economic characteristics such as manufacturing (Rust Belt) or agricultural (Breadbasket) dependence. Despite all of the variables, we innately share degrees of ideology and geographic orientation of where the American Heartland is on a map.

There is little written analysis attempting to explain the geography of the American Heartland and the emerging term, New American Heartland, in a cohesive manner. This paper explores the origin of the term, Heartland and traces through a series of predecessor terms and how the use of the American Heartland term evolved over time. It concludes with my perspectives on the geographic dimensions of defining the American Heartland.

Today, the Oxford English Dictionary defines a heartland as “a usually extensive central region of homogeneous (geographic, political, industrial, etc.) character.” Moving to the specific from the generic definition, Merriam-Webster adds a sociopolitical context to Heartland—“the central geographic region of the United States in which mainstream values or traditional values predominate.” This context is essential as the geography is deemphasized and ideology becomes more central to the definition.2 The Merriam-Webster definition also implies that some Southern states are part of the Heartland.

Further, some writers attach almost a mystical quality to the Heartland, “The Heartland is considered a place we return to when we need to renew ourselves or recommit ourselves to the things that matter.” This quote from Frontiers to Heartland provides a clear perspective of those seeking to enhance the importance of Heartland in the national psyche.3 Additionally, it suggests that Heartland residents are more stable, cautious and traditional than other parts of the U.S. Many Coastal residents would envision that description as highlighting what traits are holding the Heartland back.

"Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland; who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island; who rules the World-Island controls the world."

Halford Mackinder

Origins of Heartland

Many Americans are not aware of the historical origins of the Heartland term. The expression was first introduced by the eminent British political geographer Sir Halford John Mackinder in his 1904 paper, “The Geographical Pivot of History.”4 Mackinder classified the northern central area of Eurasia as the “pivot region” or “Heartland” of the world possessing the natural resources and rich agricultural soil necessary to obtain economic hegemony. Once gaining economic dominance in the Heartland plain, an ascendant military power could conquer not only Europe and Asia but also all maritime lands including other continents. Control of the Heartland could be the springboard to world domination. Ominously, Wilhelmine Germany, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union would attempt to realize Mackinder’s theory.

A number of years would pass before Heartland would appear in the U.S context. However, George Washington may have been among the first to envision the concept of an American Heartland. Washington, under the command of British General Edward Braddock, fought in the French and Indian Wars. He traveled to Western Pennsylvania and became familiar with the vast potential of the frontier of his era. After the Revolutionary War ended, Washington desired to facilitate commerce with the growing interior of the nation.5 While Washington predated the Heartland term, his efforts laid the political and economic case for what would become the Louisiana Purchase. A paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research states, Washington “contemplated a canal that would connect the Potomac River to the Ohio River Valley and the western states.”6 The project commenced but rising debt service difficulties killed Washington’s great waterway to the west in the 1820s. Sadly, the canal was never completed. A new technology, railroads, was about to be deployed and fulfill Washington’s vision.

Middle of the West

A considerable number of Americans believe that the term Midwest originated in the 1820s or 1830s in reference to the Ohio Valley region. Instead, the term initially known as the Middle of the West (Midwest) only dates back to the 1880s or 1890s. Moreover, the first application of the Midwest term was in reference to Kansas and Nebraska.7 Geographically, it makes sense that Midwest pertained to these two states. Kansas and Nebraska were not being compared to Montana but were in the middle of the west. Minnesota and the Dakotas at that time were associated with the Northwest, as Texas and the Indian Territories were associated with the Southwest.

There was great optimism about the future of the Midwest, and between 1912 and 1930, its application spread to the entire north-central part of the nation. Kansas and Nebraska were receiving enormous accolades in the media and other states wanted some of the shine to rub off on them. As the nation continued to spread west, one could make the claim that Utah was really in the middle of the West. Nevertheless, the Midwest began to include Ohio, west to Kansas, and north to the Canadian border. The Midwest had a growing reputation of being steady; where non-temperamental, level-minded people chose to live.

Breadbasket

The agricultural sector cultivated another path to the Heartland with the introduction of the term Breadbasket. Originally, the term referred to the stomach or belly since bread nourishes the body through the stomach. The idea of a remote agricultural region that could provide grain to urban metropolises with existing food deficits goes back to Greco-Roman cultures.8 In the first half of the 19th Century, the Great Plains was called the Great American Desert. The 1870s offered new transportation options to the vast Breadbasket with the innovation of barges that could navigate the Mississippi river and its major tributaries, along with an expanding railroad system made the Great Plains more easily accessible. Journalist Joel Garreau made the Great Plains Breadbasket one of his Nine Nations of North America.9 The Breadbasket area (Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Oklahoma, parts of Missouri, Wisconsin, Colorado, Illinois, Indiana and Texas) established many of the values ascribed to the forthcoming American Heartland.

The Breadbasket Area

- 1Iowa

- 2Kansas

- 3Minnesota

- 4Nebraska

- 5North Dakota

- 6South Dakota

- 7Oklahoma

- 8Parts of Missouri

- 9Wisconsin

- 10Colorado

- 11Illinois

- 12Indiana

- 13Texas

Manufacturing Belt

The term manufacturing belt was an attempt to describe America’s industrial geography. As steel production rose, the demand for coal, iron ore and other minerals used in manufacturing increased. Heavy machinery and the proliferation of the American automotive industry led to an expansion in supplier industries such as glass, tires and many others. Manufacturing exploded in an area resembling a parallelogram from Baltimore to Portland (ME), west to Green Bay, south to St. Louis and east back to Baltimore.10

Access to local natural resource deposits, minimized transportation costs, exploited economies of scale and a growing consumer market coalesced to form the manufacturing belt that thrived from roughly 1870 to 1970. The vast manufacturing belt was home to blue-collar workers who considered themselves middle class. Here, the middle class could afford better housing and send their children to college on a manufacturing wage. However, after 1970, this spatial concentration of manufacturing would begin a steady decline.

American Heartland Appears

One of the earliest direct references to the American Heartland appeared in Harlan Hatcher’s 1944 book, “The Great Lakes.” Harlan painted a descriptive picture of the various waves of European migrations to towns throughout the Great Lakes in “the heartland of America.”11 The following year, an anthology of Midwestern authors was advertised as “From out of America’s Heartland comes a glorious anthology of the best in American writing.” Today, we associate the American Heartland with conservative principles; however, the authors featured in the advertisement were anything but “conservatives” of their day. History would evaluate writers Sinclair Lewis, Edgard Lee Masters and Carl Sandburg as possessing progressive attitudes.12

After World War II, business interests began to use Heartland terminology in a bid to boost Midwest economic fortunes. The American National Bank and Trust Company ran an advertisement in the Chicago Tribune in 1946 touting how everyone from around the globe was flying to the Midwest. The advertisement appears to be the first to tie together manufacturing and agriculture to the American Heartland. The ad included the language, “More and more, the entire world needs the products of America’s industrial and agricultural heartland.” Moreover, the 1949 book Granger Country focused on the history of the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad.13 A reviewer discussed how “the great American heartland serviced by the Burlington railroad from the time of the first pioneers entered the region to the present.” By the 1950s, the adoption of the term American Heartland proliferated.

Flyover Country

Interestingly, at the same time that the usage of the American Heartland terminology catalyzed positive sentiment towards the middle of the country, another term emerged wielding an opposing connotation: “Flyover Country.” This derisive term emanated from the description of an airplane traveling over an expansive desolate landmass. Around 1950, commercial, non-stop transcontinental airline flights became a reality. An article appeared in Esquire on the landscape painter Russell Chatham, which included the phrase: “Because we live in flyover country, we try to figure out what is going on elsewhere by subscribing to magazines.”14 In 1980, the first entry in Oxford English Dictionary for Flyover Country was made. Most people who reside in Flyover Country take great offense to the phrase and might initiate an exchange with the people who used it. One would say it is an insult to be depicted as a place best experienced at cruising altitude, where politicians and cultural socialites land only when they must.15

South in the American Heartland

Up to this point, while the precise definition of the American Heartland might not have been resolved, the states involved were clearly Midwestern. Southern states like Arkansas and Tennessee were not included in the American Heartland geography. The exclusion was partly attributable to the legacy from the Civil War that caused geographical division between the North and the South. Political winds were changing direction in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Kevin Philip’s 1969 book, “The Emerging Republican Majority,”16 laid out the case for how the South would no longer be a Democratic stronghold. The Chicago Tribune ran a book excerpt titled, “The Power of the Heartland and the Rise of Conservatism.” The commentary argued that the electoral legacy of the Civil War had been broken. Shifting conservative values began to draw people together blurring the divide in the middle of the country between the North and South. The article stated, “the vast American interior is drawing together as the seat of a conservative majority.”17 Shared religious values and the rise of evangelicalism played a part as well, much of which spread from the Midwest to South.

Rust Belt

Ironically, the usage of the Heartland term proliferated in juxtaposition to the emergence of the Rust Belt term in the 1980s. To some extent, journalists and other writers publicized Heartland in an attempt to counterbalance the negative connotations associated with Rust Belt. As globalization, labor disputes, rising labor costs, automation and a series of other dispersal forces rose, the manufacturing belt experienced an erosion of its key industries. The aging Rust Belt ran from New York through the Midwest. Steel, auto and other mainstream manufacturing plants closed throughout the region. Many smaller communities heavily dependent on one industry or one large employer were devastated when they shrank or shuttered.

Economic fortunes in the Heartland improved somewhat during the presidency of Bill Clinton. A nostalgic connotation associated with the Heartland term became more relevant to a set of ideals and lifestyle than a specific, well-defined geographic region. People spent less time articulating which states constituted the Heartland, and more on cultural, attitudinal and religious aspects of its meaning. As a Forbes article states, “It’s a very diverse place…a very diverse culture bound together by a core set of values such as faith, community and family.”18

The South Evolves

During the 1990s and in subsequent years, transformational changes in the industrial geography drew Southern states into the American Heartland. Japanese automakers, Toyota and Nissan located auto-manufacturing plants in Kentucky and Tennessee to circumvent charges of unfair trading practices. The auto plants integrated the economies of the Midwestern Heartland with the South. The North-South automotive supply chain expanded and the linkages drew Kentucky and Tennessee into acceptance of being “heartland.” As German automotive firms soon expanded into Mississippi and Alabama, they began to be associated with “Heartland” thinking. The first evidence of Arkansas and Oklahoma’s inclusion to the Heartland was in a 1988 Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas article titled, “Economic Development: A Regional Challenge for the Heartland."19 Soon, Louisiana began to be referenced in the American Heartland context. A 2009 paper, “Déterminé l'Effacement: The French Creole Cultural Zone in the American Heartland,” indicated a sense of comfort and a greater awareness to include Louisiana.20

Pre-and Post-2016 Presidential Election Heartland

The American Heartland reclaimed the spotlight leading up to the 2016 Presidential election. The rising economic, cultural, and other fissures between the Heartland and the Coasts had been apparent for some time, but presidential candidate Donald Trump chose the campaign slogan, “Make America Great Again,” with the intention of seeking disgruntled voters in the Heartland. When many Heartland voters heard the terms “globalization” and “trade agreements,” they perceived the words to be forces that helped everyone else but harmed them.

Dissonance grew between many Heartland and Coastal residents leading to heated debates that attracted immense media attention. Moreover, it created circumspection on what debating parties meant when they referred to the Heartland.

Opposing Geographic Definitions

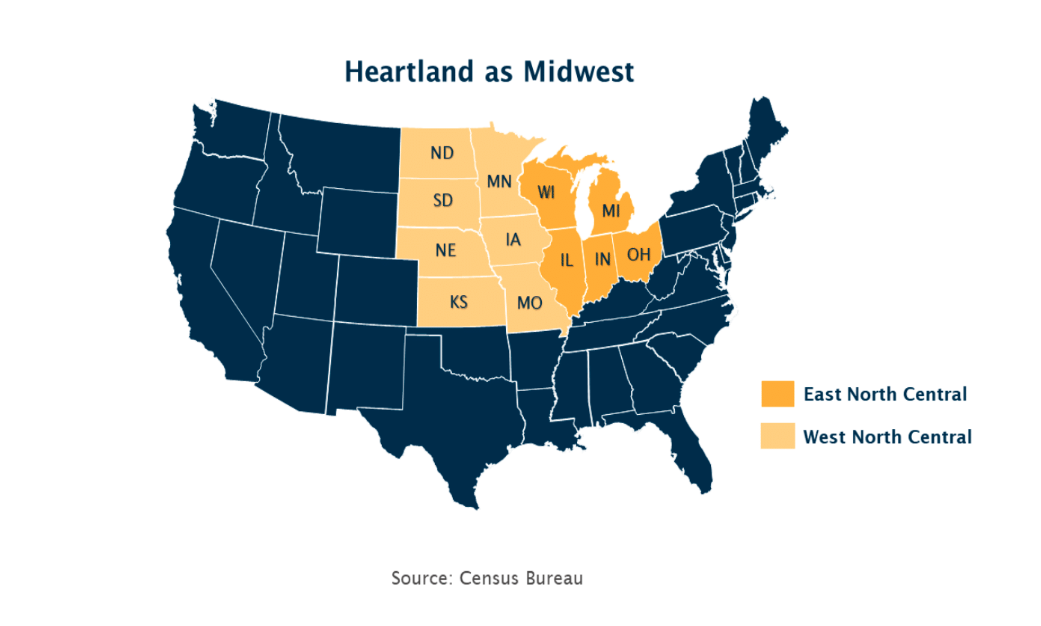

What are the opposing geographic definitions of the Heartland? There are still many that believe the Heartland refers to a geography of the Midwest (especially those born in and residing in the Midwest). The specific geographic dimension would include the Census Bureau’s East North Central (Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois and Wisconsin) and West North Central (Missouri, Kansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, South Dakota and North Dakota) Regions.21 A February 2018 article in Heartland Tech titled “Remote work offers the Heartland an opportunity to transcend geographic constraints,” discusses how real incomes in the Midwest (Heartland inferred) have fallen. In 2016, the average Midwest family saw their real incomes decline 14 percent from 2000 levels. The article pointed out how all other regions of the country witnessed a rise in real incomes over the period.22 Further highlighting that poor Midwesterners are living shorter lives than comparably defined poor in other parts of the country.

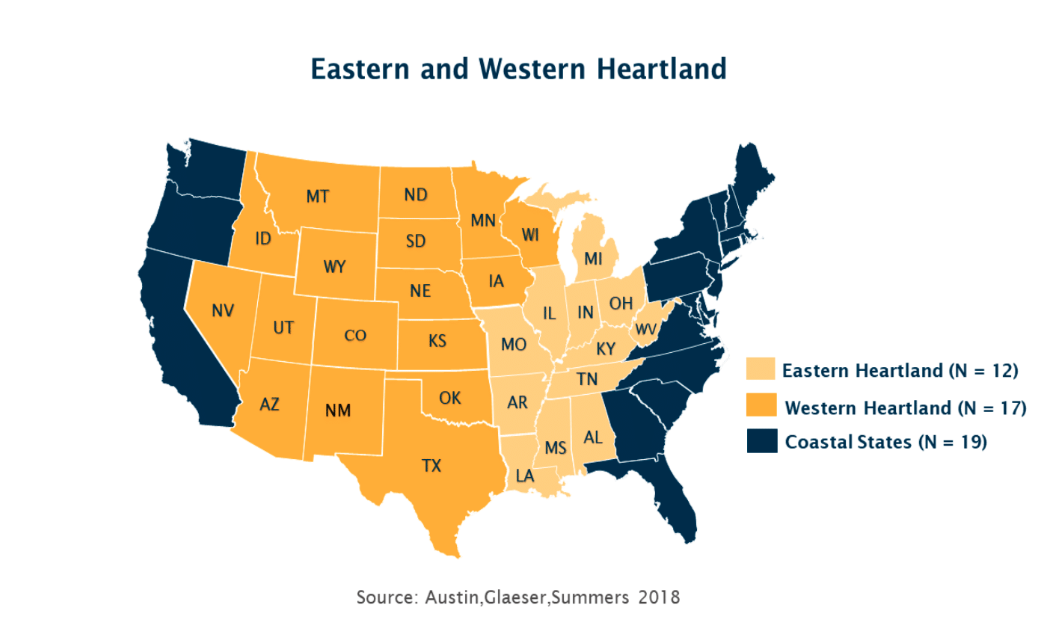

Harvard economist Ed Glaeser, who is best known for his work in regional economics, has teamed with Harvard University colleagues Larry Summers (former Treasury Secretary under President Clinton, former Harvard President and former head of the National Economic Council under President Barack Obama) and Benjamin Austin to articulate some policy prescriptions for the Heartland. Among other policy ideas, they postulate that the federal government needs to move from only helping people in places, to assisting the places in which they reside. In a March 2018 paper for Brookings Institute, the trio offers a distinct definition of the Heartland and break it into two regional components: an Eastern and Western Heartland.23

In many respects, it is easier to define what the Heartland is in Glaeser’s definition by stating what it is not. His Coastal States in the east stretch from Maine down the Atlantic Seaboard to Florida–basically the original 13 Colonies plus Florida–adding in Washington, Oregon and California.

We divide the U.S. into three regions: the prosperous coasts, the western heartland and the eastern heartland. The coasts have high incomes, but the western heartland also benefits from natural resources and high levels of historical education. America’s social problems, including non-employment, disability, opioid-related deaths and rising mortality, are concentrated in America’s eastern heartland, states from Mississippi to Michigan, generally east of the Mississippi and not on the Atlantic coast. The income and employment gaps between three regions are not converging, but instead seem to be hardening ...

Respectively, the Eastern Heartland includes Michigan, Ohio, West Virginia, Indiana, Kentucky, Illinois, Missouri, Tennessee, Arkansas, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana. Basically, all non-coastal states that were admitted to the Union before 1840.24 The Western Heartland includes the rest of the center of the country through the Mountain States. By this definition, the American Heartland is a vast spread of land mass that seems too broad and arbitrary. While they point to many statistics highlighting numerous distinctions between the three regions and within the Heartland, an almost equal number of metrics reveal that there is no statistically significant distinction from each other. There is no other reference depicting Idaho, Nevada and Arizona as part of the American Heartland.

New American Heartland

Recent attempts have been made to develop a geography called a New American Heartland. Usually, this encompasses a noted shift in manufacturing and logistics patterns in the country accentuated by the North American Free Trade Agreement’s (NAFTA) extension into Mexico. Joel Kotkin and colleague Michael Lind make the case in “The New American Heartland: Renewing the Middle Class by Revitalizing Middle America."25 They see the New American Heartland as the center of country’s productive economy.

“The boundaries of economic regions are subjective and imprecise. Still, an image of the Gulf of Mexico watershed suggests the rough shape and dimensions of the North American economic core we are calling the New Heartland. This redefinition of the Heartland recognizes a shift in the changing nature of America’s ‘core’ and its periphery… The automobile industry, America’s most important manufacturing field, was reshaped as Japanese, German and South Korean automobile companies opened up plants in the US. Some of these ‘transplants’ were in the Midwest, others were in a new automotive belt stretching across the southeastern U.S., Texas and Mexico. In shipping, the Gulf Coast became one of the fastest growing U.S. ports. The stage was set for a new phase in America’s economic history: the emergence of a New American Heartland.”

The above definition includes the Midwest, and a broad swath of the South including Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and Florida. Texas is also included in the New American Heartland. The case for Texas is based upon new manufacturing zones located in the state. A strong case is made for Georgia, but Florida does not seem to fit the New American Heartland profile particularly well.

Others have examined the “New” Heartland depiction through the lens of marketing concepts to develop their geographic definition. Paul Jankowski started a new brand-consulting group based upon research from his 2011 book, How to Speak American: Building Brands in the New Heartland.26 “It means different things to different people who live here. To some, it is amber fields of waving grain and pickup trucks or a bustling city with a lively arts scene and hip clubs. To others, it’s “Friday night lights” and fried chicken with family on a Sunday afternoon.” Social characteristics such as religious beliefs or faith is another important determinate. Belief in the importance of religion, worship service attendance, frequency of prayer and absolute certainty in the belief of God seem to be predictive of consumer purchasing patterns and display a geographic manifestation. Therefore, New Heartland is more about lifestyle and ideals than geographic borders. He acknowledges, however, that without some geographic base, it is an indeterminate, undefined, conceptual place. Jankowski ultimately says the New Heartland is 26 states bounded from North Dakota, south to Texas, east to Florida (except South Florida), up the Atlantic Coast to Virginia (excluding the D.C. metro area), to West Virginia, Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota.

What to Conclude?

If one focuses on traditional values rather than geography, the Central Valley of California and portions of Texas are part of the American Heartland. However, if one draws an inference from the Merriam-Webster definition, the Heartland must be limited to a central geographic region ruling out the Central Valley. Additionally, sub-state area definitions create confusion, they are messy and we would never reach an agreement. The expansive Heartland with Eastern and Western regions is a real stretch. Maybe it is Flyover Country, but it is preposterous to call those states the Heartland.

The boundaries of the American Heartland must include parts of the South as many are central, but I cannot include any of the original 13 American Colonies. By definition, you cannot be in the Heartland if you were a member of the 13 Colonies. Yes, that rules out Georgia and West Virginia because it was part of Virginia, even though culturally, they share many Heartland values. Florida was not a member of the original 13; but the state just cannot be in the Heartland as it has an Atlantic Coastline, so it must be part of the coast.

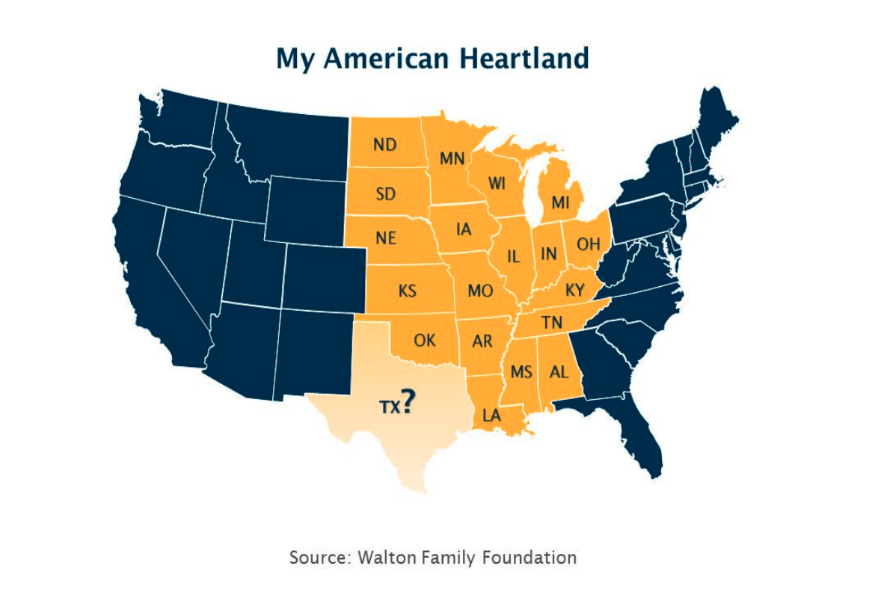

To me, the American Heartland includes the Midwest (defined by Census Bureau Regions of the East North Central and West North Central) and the East South Central (Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama and Mississippi).

Additionally, I would include Arkansas, Oklahoma and Louisiana in the West South Central. If I were to add “New” to American Heartland, I would include Texas, capturing all of the West South Central Region making the area a clear combination of four Census Regions with Central in their title. This matches the Merriam-Webster definition of the center of the country precisely. Even without adding “New,” Texas makes a strong case to be included in American Heartland especially based on their measures of faith. Most native Texans can sing the lyrics to Heartland. If a Texan thinks they are part of the Heartland, how could I tell him or her they are not? Most people would agree that George Strait, Field of Dreams and the Pioneer Woman all strike chords of my version of the American Heartland.

Endnotes

-

Badger, E., & Quealy, K. (2017, January 03). Where Is America's Heartland? Pick Your Map. Retrieved from nytimes.com/interactive/2017/01/03/upshot/where-is-americas-heartland-pick-your-map.html

-

Higbie, T. (1970, January 01). Global Heartland. Retrieved from globalheartland.blogspot.com/2006/12/why-did-midwest-become-heartland.html

-

Imagined Heartland. (n.d.). Retrieved from publications.newberry.org/frontiertoheartland/exhibits/show/perspectives/rethinkingheartland

-

Mackinder, H. J. (April 1904). The Geographical pivot in history (1904). The Geographical Journal, 170(No. 4). Retrieved from iwp.edu/docLib/20131016_MackinderTheGeographicalJournal.pdf.

-

Achenbach, J. (2004). The Grand Idea: George Washington’s Potomac and the Race to the West. Simon and Schuster.

-

Glaeser, E. L., & Gottlieb, J. D. (n.d.). The Economics of Place-Making Policies. Retrieved from nber.org/papers/w14373 NBER Working Paper No. 14373 Issued in October

-

Shortridge, J. R. (June/July 1998). The Heartland's Role in US Culture: It's "Main Street". The Public Perspective, 40-42. Retrieved from ropercenter.cornell.edu/public-perspective/ppscan/94/94040.pdf.

-

Wishart, D. J. (n.d.). Encyclopedia of the Great Plains , Breadbasket of North America. Retrieved from plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.ii.006

-

Garreau, J. (1981, September). The Nine Nations Of North America - The State Historical ... Retrieved from bing.com/cr

-

Klein, A., & Crafts, N. (2011, August 25). Making sense of the manufacturing belt: Determinants of U.S. industrial location, 1880–1920 | Journal of Economic Geography | Oxford Academic. Retrieved from academic.oup.com/joeg/article-abstract/12/4/775/946998

-

Hatcher, H. (2018, May 01). The Great Lakes Oxford University Press (1944). Retrieved from worldcat.org/title/great-lakes/oclc/1016015

-

Higbie, T. (2007, January 03). Global Heartland. Retrieved from globalheartland.blogspot.com/2006/12/why-did-midwest-become-heartland.html

-

Lewis, L., & Pargellis, S. (n.d.). GRANGER COUNTRY, A Pictorial Social History of The ... Retrieved from bing.com/cr

-

McGuane, T. (1980, March). Big Sky, Big Swamps. Retrieved from archive.esquire.com/issue/19800301

-

Bullard, G. (2016, March 28). The Surprising Origin of the Phrase 'Flyover Country'. Retrieved from news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/03/160314-flyover-country-origin-language-midwest

-

Phillip, K. (n.d.). The Emerging Republican Majority: Kevin P. Phillips ... Retrieved from

bing.com/amazon.com/EmergingRepublican-Majority-Kevin-Phillips/dp/0870000586&p=DevEx.LB.1,5074.1. -

Higbie, T. (2007, January 03). Global Heartland. Retrieved from globalheartland.blogspot.com/2006/12/why-did-midwest-become-heartland.html

-

Jankowski, P. (2011, August 09). Defining the New Heartland. Retrieved from forbes.com/sites/pauljankowski/2011/06/14/defining-the-new-heartland

-

Fosler, R. S. (1988, January 01). Economic development: A regional challenge for the heartland, by R. Scott Fosler. Retrieved from ideas.repec.org/a/fip/fedker/y1988imayp10-19nv.73no.5

-

Moore, B. (n.d.). Déterminé l'Effacement: The French Creole Cultural Zone in the American Heartland. Retrieved from lesamis.org/downloads/moore_bob-revised_french_creole_cultural_zone_ws_final.pdf

-

Census Regions and Divisions of the United States. Retrieved from www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/mapsdata/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf

-

Kasriel, S.(2018, February 14). Remote work offers the Heartland an opportunity to transcend geographic constraints. Retrieved from venturebeat.com/2018/02/14/remote-work-offers-the-heartland-anopportunity-to-transcend-geographic-constraints

-

Austin, B., Glaeser, E., & Summers, L. H. (2018, March). Saving the heartland: Place-based policies in 21st

century ... Retrieved from bing.com/brookings.edu/wpcontent/uploads/2018/03/3_austinetal.pdf&p=DevEx.LB.1,5497. -

Smith, N. (2018, March 13). A Better Way to Revive America's Rust Belt. Retrieved from bloomberg.com/view/articles/2018-03-13/a-better-way-to-revive-america-s-rust-belt

-

Lind, M., & Joel, K. (2017, May). The New American Heartland: Renewing the Middle Class by Revitalizing the

Heartland. Retrieved from newgeography.com/content/005616-the-new-american-heartlandrenewing-middle-class-revitalizing-heartland -

Jankowski, P. (2011). How to speak American: Building brands in the new heartland. Brentwood, TN: ABS Publishing Company.